“Parts Work” Isn’t New. It is Ancient.

When I introduce clients to Internal Family Systems therapy, many are surprised to learn that working with "parts" isn't a modern invention. The recognition that human consciousness contains multiplicity (distinct inner voices, impulses, and aspects with their own agendas) is one of humanity's oldest psychological insights.

Before we work together, I want you to understand the rich lineage you're stepping into. This isn't a therapeutic trend or a clever reframing technique. It's an ancient truth that has been recognized, honoured, and worked with across cultures, philosophies, and healing traditions for thousands of years.

Medieval mystics like Teresa of Avila described the "interior castle" of consciousness with its many rooms - different chambers housing different aspects of the soul that needed to be visited, understood, and integrated on the path to wholeness.

Inner multiplicity is also recognised by Eastern and Indigenous spiritual and healing traditions. For instance, Buddhist psychology teaches that what we call "self" is actually a collection of aggregates (skandhas) and that consciousness contains multiple minds (the desiring mind, the aversive mind, the deluded mind, the concentrated mind). Meditation practice involves observing these different states arise and pass without identifying with any of them.

Indigenous shamanic traditions across the Americas, Asia, Africa, and elsewhere have practiced "soul retrieval" - the understanding that trauma causes parts of the soul to fragment and flee, and that healing requires retrieving these parts and reintegrating them.

The universality is striking. Across vastly different cultures, separated by oceans and millennia, humans have recognised the multiplicity of consciousness and developed practices for working with it.

Philosophers and ancient traditions recognise what you probably already know from your own experience: you are not singular. You are multiple, and learning to work with that multiplicity is central to psychological and spiritual maturity.

Early Psychology: Mapping Inner Multiplicity

When psychology emerged as a formal discipline in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the question of inner multiplicity became central.

Sigmund Freud's structural model (the id, ego, and superego) was perhaps the first modern psychological framework to formalise what philosophy had long intuited. These weren't just concepts to Freud; they were distinct agencies within the mind, each with its own logic, energy, and intentions. The id pursued pleasure, the superego enforced moral restrictions, and the ego mediated between them and external reality. Freud understood that internal conflict was structural, and built into how minds work.

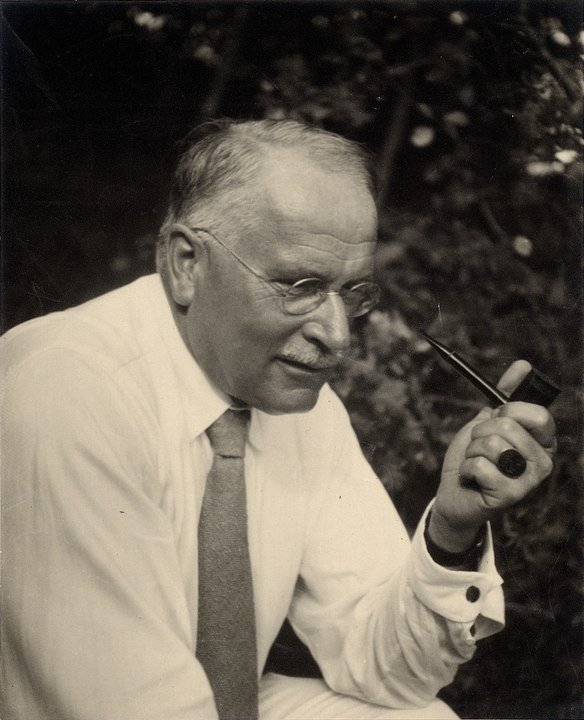

Carl Jung went further, developing a sophisticated understanding of what he called "complexes." Jung observed that complexes behaved like "splinter psyches" (semi-autonomous entities with their own emotional charge, memories, and behavioural patterns). When activated, they could temporarily "possess" consciousness, determining how we perceive and respond to situations. His work with active imagination involved dialoguing directly with these aspects of the psyche, including personifying them, listening to them, allowing them to reveal their nature and needs.

Jung also explored archetypes. These are universal patterns like the Shadow, the Anima/Animus, the Wise Old Man that are as autonomous energies within the collective unconscious. These weren't merely symbolic; Jung believed they had genuine psychological agency.

When I work with your inner critic or your wounded child, we're walking in Jung's footsteps, recognising that these patterns have their own life within you.

The Object Relations theorists of the mid-20th century added understanding about where parts come from.

For example, W.R.D. Fairbairn proposed that we internalise our early relationships, particularly the difficult ones. When a parent is sometimes nurturing and sometimes critical, the child's psyche splits these experiences into separate "part-objects" (the good parent and the bad parent) which then become aspects of the internal world. These internalised others continue to operate within us, creating inner dialogue and conflict.

Donald Winnicott explored the "false self" - a compliant, adaptive part that develops to protect the "true self".

Melanie Klein described internal objects that could be loving or persecutory, and the infant's task of integrating these split representations. Her work revealed that even very young children experience their inner world as populated by distinct presences.

When you and I work with the part of you that internalised a critical parent's voice, or the part that learned to please others to stay safe, we're applying object relations insight: significant relationships don't just influence us. They take up residence inside us as parts.

Formal Parts-Based Therapies

By the mid-20th century, several therapeutic approaches had formalised parts work.

Psychodrama, developed by Jacob Moreno in the 1920s, invited clients to embody different roles and perspectives, including aspects of themselves. Moreno understood that externalising internal conflicts allowed for new relationships and resolution. During therapy when I ask you to notice where you feel a part in your body, or to speak from a part's perspective, we're using principles Moreno established a century ago.

Fritz Perls and Gestalt Therapy (1940s-50s) made "parts work" even more explicit with the empty chair technique. Perls would have clients literally move between chairs, embodying the part that wants something and the part that resists, the critical part and the defended part. He recognized that integration happens through dialogue, not through one part dominating another.

Transactional Analysis, developed by Eric Berne in the 1950s, gave us Parent, Adult, and Child ego states. These are distinct modes of being that we shift between, each with its own feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. Berne taught people to recognize which ego state was "executive" in any moment and to develop Adult awareness that could observe and coordinate the others.

Ego State Therapy, formalized by John and Helen Watkins in the 1970s-80s, provided a direct precursor to IFS. The Watkinses worked explicitly with "ego states” or parts of personality that could be activated, interviewed, and worked with therapeutically. They developed techniques for helping conflicting ego states negotiate with each other and for healing traumatised states. If you've encountered IFS, you'll find Ego State Therapy remarkably similar in method and philosophy.

Roberto Assagioli's Psychosynthesis (early 1900s) deserves special mention. Assagioli explicitly worked with "subpersonalities”, each with distinctive characteristics, desires, and fears. Like IFS, Psychosynthesis emphasised a central "I" or Self that transcends subpersonalities and can coordinate them with compassion. Assagioli taught techniques for identifying subpersonalities, dialoguing with them, and helping them harmonise.

Why does it matter that parts work predates IFS?

When we understand that multiplicity has been recognised across therapeutic approaches, cultures and history, we touch something universal about human consciousness: we are multiple.

So what does IFS add to this ancient, global lineage?

Normalisation. IFS made multiplicity unambiguously healthy and universal. Not "some people have parts due to trauma," but "everyone has parts, and that's how minds work." This reframe alone has been profoundly healing for countless people who thought their inner multiplicity meant something was wrong with them.

Clarity. IFS offers a model and clear starting point for understanding the inner world. Part of this model includes general patterns of parts (managers, firefighters, and exiles) that help organise what might otherwise feel like overwhelming inner chaos.

Accessibility. By creating clear language and structured methodology, IFS made parts work accessible to therapists across theoretical orientations and to their clients.

What IFS gave us was a particularly clear, structured, and compassionate approach to timeless truth.

The Invitation

Whether you call them parts, subpersonalities, ego states, complexes, or simply different aspects of yourself, the invitation remains the same: turn toward your inner multiplicity with curiosity rather than judgment.

Your inner world isn't a battlefield where one part should vanquish the others. It's a system, a community, an ecology, and one that functions best when all parts feel seen, valued, and welcomed at the table of your consciousness.

IFS didn't invent this truth, but it gave us an approach to understanding. And in a culture that often demands we present as singular, consistent, and uncomplicated, remembering our multiplicity might be the one of the most powerfully healing things we can do.

If you're ready to explore your parts and curious about what IFS therapy might look like for you, I'd be honoured to work with you. Book a free 20 minute consultation to get started.

Explore more articles:

Why You Keep Getting In Your Own Way (And What To Do About It)